Mosaic Music

The perforated line between music and life, and the Rearranged episode I didn't make

"Pieces of Time Torn from the Cosmos"

Before telling you about the Rearranged episode that is coming out today, let me tell you about the one I didn't make.

It had a good title: “Pieces of Time Torn from the Cosmos.”

That's not mine. Pierre Schaeffer used it to characterize musique concrète.

When Thomas Edison conceptualized the phonograph, "reproduction of music" was number four on a long list of potential uses, from "letter writing and all kinds of dictation without the aid of a stenographer" to "clocks that should announce in articulate speech the time for going home, going to meals, etc." to "the 'Family Record'—a registry of sayings, reminiscences, etc., by members of a family in their own voices, and of the last words of dying persons."

Since the phonograph's invention, a thread has run through the recording endeavor of artists intentionally perforating the line between music and life.

Sampling may come to mind first. However, that is just a part of the perforation. Technology makes this act easier every day, but used to be a lot of work, like the work that took place in Schaeffer's Groupe de recherches de musique concrète, where, as early as 1950, composers worked with engineers, philosophers, and psychologists to organize everyday noises into meaningful sound.

This is a natural act. Children do it.

Go back further: does Walther Ruttmann's 1927 film Berlin: Symphony of a Great City not, despite being silent, insinuate an hour of the music of life?

More popular instances of this musical approach include Steve Reich's "Come Out" and "Different Trains," and, of course, The Beatles' "Revolution 9."

A Natural Act

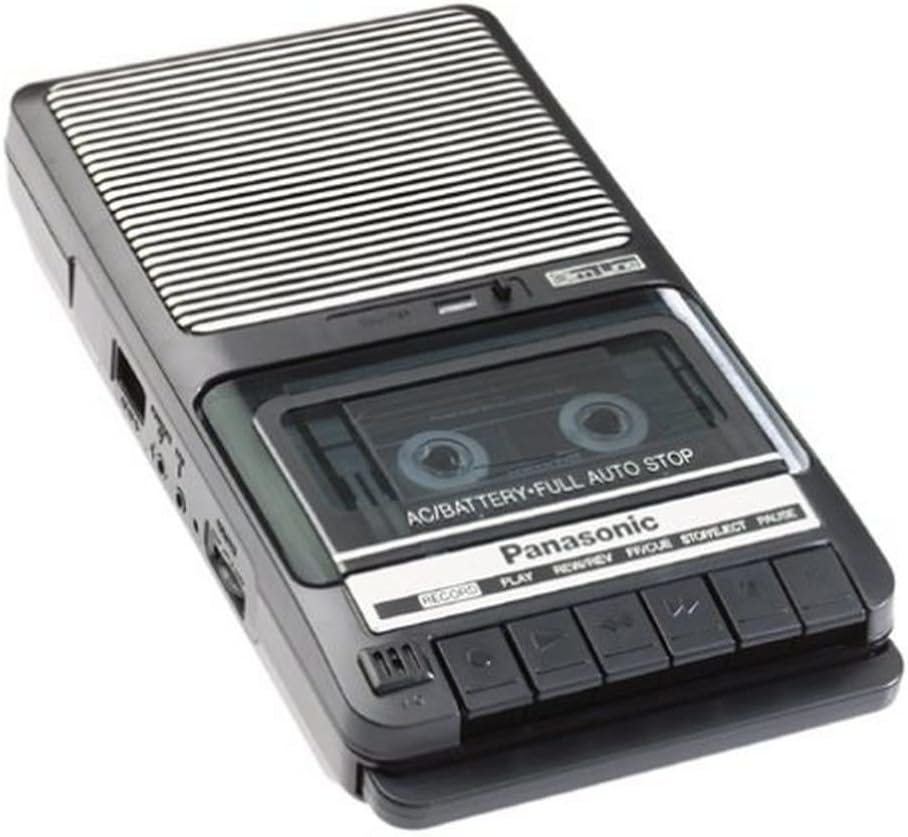

This is a natural act. Children do it. My friends and I had "tape recorders"—mine was a Panasonic, which I later used as a car stereo in my 1978 Buick when I got my license—and although we sometimes recorded hits off of B-104, our Top 40 station, we were just as likely to record goofy noises, the prosaic din of the household, jokes and skits, and other unremarkable aspects of a day in the life.

Without my quite realizing it, this approach to music making shaped some of my favorite recordings over the years. On Madvillain, probably my favorite album of the '00s, Madlib hilariously samples Reich's "Come Out" (a sample of a sample!) as an intro to "America's Most Blunted," a big dumb weed song (big dumb and perfect).

The 2003 album Goodbye Swingtime by Matthew Herbert (who I just discovered was, unsurprisingly, remixed by Matmos) had me upside down with its fractured digital rearrangement of big band music that Herbert had written and recorded. It was mosaic music, but some of the pieces were big. After shattering the sound of the big band, Herbert would let some Gil Evans- or Henry Mancini-sounding joint just run with little disruption.

A lot of this fractured field recording thing was going on around then, maybe because digital tools were becoming more accessible. The Books made a splash in the early aughts, and Matmos's A Chance to Cut is a Chance to Cure came out in 2001.

A few years later, Dave Longstreth did something similar with his Dirty Projectors album The Getty Address. (A treasured memory: one of my first dates with my wife, seeing Dirty Projectors play The Getty Address at The Cake Shop on the Lower East Side.) Once a composition student at Yale, Longstreth recorded classical musicians for The Getty Address, chopped the tape, and did literal arranging of the pieces. In 2018, Makaya McCraven chopped fairly free jazz improvisations into gripping grooves and beats on his album Universal Beings.

"What is Possible?"

Writing this, I realize I patrol that border between music and life, keeping each on its supposedly proper side. Often, I feel like I turn away from life when I turn to music and turn back to it when I'm done. I'm not sure that's healthy. Eventually, though, I fall for the sounds that are slow to reveal which is which. When Matmos samples Jason Willett plucking a rubber band, is that music or life? A groove or office supply management?

To excuse yourself from traditional musical tools and concepts is to invite the listener to ask, with you, "What is possible?" I've done it a few times: it's exhilarating. On Disappearing Ink's "All Some None," I chopped up a 12-year-old free guitar improvisation and added a new arrangement to it, including drums. It led me to rhythms and sounds I never would have considered. On "Die Laughing," I made five or six recordings of myself laughing (at nothing, alone in my studio), found some rhythm in them, and stitched together a beat.

On "Cockamamie Cat," I built a song out of samples of Elliott Gould feeding his cat at 3 a.m. in The Long Goodbye. Complicating the sample was the lounge-y take of John Williams's theme music. If I sampled Gould, I was stuck with the beginning and end of the score I'd chopped with him. But serendipity offered me perfectly capped rhythms. I also captured a woman's breathing in one of the Gould samples. An inhale is the beginning of a note, and an exhale is the beginning of a note. It didn't matter where the breaths stopped and started, it sounded good...just a matter of how many beams and dots to add.

An inhale is the beginning of a note, and an exhale is the beginning of a note. There's the place to hang: where life is music and music is life.

Evolution in Recording Technology, Revolution in Song

All of this is to say that the new episode of Rearranged is out. It's about how drastically the sound of the popular song has changed over the past 150 years, and how much of that has to do with the evolution of recording technology.

In the days of Tin Pan Alley, if you wanted to hear a popular song, someone had to play it for you, or you played it for yourself. This episode starts with the first million-selling piece of sheet music and makes its way through ribbon mics, multitracking, samplers, and up to the 21st century technology that has democratized music making.

We'll hear about Bessie Smith, Rudy Vallee, Bing Crosby, The Beach Boys, Marley Marl, Public Enemy, and many more artists. (Listen real close and you'll hear Can, Carla Bley, and Funkadelic.)

I talk to Susan Schmidt Horning, who played in 60s "girl bands" and later became a professor who wrote a history of the recording studio.

One highlight of producing this episode was working with Brandon Shaw McKnight. After seeing him act and sing at a Chesapeake Shakespeare Company production, I booked him to act and sing in a dramatization at the beginning of this episode.

This episode also features the producer, DJ, music journalist, and Philadelphian John Morrison. John and I discover that despite all the technological changes, there are some things about a great song that never change.

I hope you have as much fun listening to this episode as I spent producing it.

Thanks as always to Osiris Media for marketing and distribution.